carried . shared . remembered

As we migrate we carry the narrative of food from home in an ever-changing script. As we grow, change, learn, and experiment, our food changes too. But the heart of it is always home.

Food, is written about and prepared and shared as a small performance - a signal on a plate, a statement, a message forked into the world, saying look at this, here is my offer. See what I stand for. See where I came from. Where my people were. What I love. What I miss. The scents and tastes I long to share with you.

What we choose to cook and eat is like a narrative in an ever-changing script. As we grow, change, learn, and experiment, our food changes too. But the heart of it is always home. The foundational plates on our table are about sharing our homes with each other.

So many of my friends are immigrants or daughters and sons of recent immigrants to the USA. They come to my farm in Illinois to cook with real food. Many I met when I had woofers come to work on the farm or when I ran an Airbnb. Many I met through my old blog.

But they all brought their own histories into my gardens and into my kitchen. They brought their own stories of the journeys to the shores of America. And they brought their own histories food from home.

My Italian friend John from Chicago taught me how to make pasta. He would come down to the farm kitchen with his roller and his ancient ravioli forms to make piles of ravioli to freeze for hay making season.

My friend Fede would feed us food from his home in Argentina. To educate us and delight us but also because he was homesick for meals from his home land. His chimi churri is still made exactly like this - wherever I am.

The weekend (I began writing this after the bombings of Iran by the USA) made me immediately want to make Iranian food, but I have not cooked those ancient Persian dishes, so my mind drifted to a yoghurt method from a good friend who lives in Jordan - nowhere near Iran. But geography was never my best subject.

Driving from Iran to Jordan would be a long winding push west - I have never been - but my sister spent time out that way - you go through mountains and deserts, past border posts, and security check points and long silent stretches of road. You leave Iran’s rugged plains behind, cross into Iraq or Syria (depending on the route and the politics of the day), then drop down into Jordan where my friend lives.

My Jordanian friend taught me how to make yoghurt without any gadgets. She taught me to make yoghurt in a big pot without measuring a thing: fill the pot with fresh milk from my cows, heat it to very hot- just to the first bubble - then cool it to hand warm. Add a quarter cup of yoghurt from the last batch, swirl it with a little warm milk, then stir the slurry into the pot. Stir ten times, cover with blankets to keep warm, and leave it on the kitchen table to work.

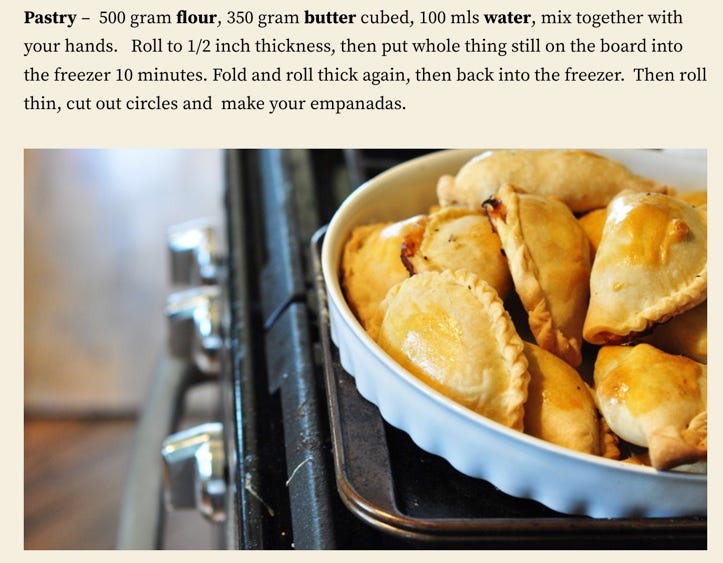

I made bread while I was thinking - I always think best when kneading dough and today I am making pasties. Which made me think about empanada.

Hugo who arrived from France with not one word of English, I taught him English and how to drive a manual car and he taught me how to make crepes with his grandmothers recipe which he ate with Nutella filling one with ham and cheese for me because I am not a sweet person. And croquettes. I need to make croquettes again soon!

Federico (the one from Argentina) also spent three months with me learning English on the farm. What interested me was that when he made empanadas for us he always added grated boiled egg to the meat mixture.

These reminded me of the Scottish pasties that Mum used to make back in the 70s.

Mum used a similar shortcrust recipe to Fede. Worlds and generations apart. But filled her tasty stodgy pasties with root vegetables: potato and parsnip and carrot and a little mutton. When I make Mum’s pasties I thicken the mixture with cornstarch - I know that is cheating but my grandma’s pies, my mothers pies - my Dad’s Mum had a pie shop while his Dad was away at the war - all these women used cornflour (cornstarch) to thicken. (And tapioca mixed with the meat in times when meat was scarce during the war). We are 6th generation New Zealanders from Irish and Italian descent - so long ago but I can still detect the scent of old Irish ways in our family food. (The immigrants who arrived on ships). Yet here I am talking about a Scottish dish that we ate often.

My mind wandered along the lines of hand pies even further and I remember fatayer taught to me from my friend Rosy from Beirut- fatayer are like little calzones—stuffed with spinach, onion, sumac, and olive oil, then baked until golden. She collected spinach from our garden. She would bring little jars of spices from her grandmother who lived in Lebanon and cook with them. I still have some of the sumac from her grandmother back in the country kitchen in Illinois.

The spinach made me think of Spanakopita which I ate almost daily when I was on a rock climbing holiday in Greece. Which made me think of the calzone I used to eat when I worked on a film crew on the Amalfi Coast in Italy.

Over the years my international immigrant friends have taught me to make so many different foods; these Pasties and Empanadas and Calzones and Fataya are only a few. Similar pastry and similar fillings and similar shapes but vasty different spices and aromatics. From incredibly different regions. All this food teaches us about history and beliefs and regions and environments. It performs for us. It makes us. It teaches us how big the world is and how rich and generous are most of the people in it. Especially travelers.

The pies I make are not pretty but are more like Crimean Chebureki than anything else because I LOVE flaky crunchy light pastry. An Albanian friend of my father’s would bring pies like these when he visited the house at the beach in New Zealand. Dad was never sure how an Albanian knew a Crimean dish but people move about a lot - that’s what they do. Migration of peoples is old. Emigration and immigration is ancient. And often food is the most honest way to trace their journey.

My little pies brought to mind Anna whose Polish mother came out after the war to work in the Chicago as a nurse. Her Polish grandmother was experimented on by the Nazi’s during the war - they would insert something under her skin then cover it with a bandage to see if the fungus or mould grew into her body. She was threatened that she must not touch the bandage. She would go about her day with this patch on her thigh then report back in each week so men could inspect the growths. Anna did not know much more, as her mother would not speak of it. They were shamed. But Anna told me her grandmother carried scars from these experiments. Anna used to come down to the farm to spend time with the animals and would make us the classic pierogi ruskie and we would scoff them with home made labneh taught to me by an American boy who used to work in a Turkish restaurant using the yoghurt taught to me by my friend from Jordan spinkled with the a little of Rosy’s Sumac from Lebanon.

The traces of immigration are in our foods everywhere. Breakfast taco’s sold on the side of the road in the morning in Visalia, California. Little Ukrainian vareneky made by a friend of my sons who brought her family out of war-torn Ukraine a couple of years ago, she and I spent time together in California working on her bread making and now she has opened a bakery there.

All immigrants tell their stories in food. Telling their journey. Food is more than fortification - it is a place of home carried in their bodies. Made with their hands. We need to listen and learn and share.

And as I am a New Zealander with a US green card staying in Australia at the moment we must not forget New Zealand meat pies - about the size of your hand, that you buy at the service station or bakery and eat straight out of the bag but don’t eat too fast because pies are served nuclear hot! My favourite is steak and cheese. Of course!

I could not find these pies in Illinois so I have taught many Americans and immigrants and visitors to America how to make them and they have taken this knowledge back to their own people across the states and into South America and Europe. And so the New Zealand pie is spread across the world by an immigrant to the USA. Our food is important. Our journeys are critical learning. Sharing this is an act of joy and deep love. We should not be ashamed of our travels - our yearning to do better. Live better.

Each of these little pies, these pastry wrapped foods to hold in your hand, were first made in far-away places, often folded into paper or linen and taken to work for the day, and they perform small dances of memory for us. This global story. This whisper of family. Tracking journeys. Nodding through windows. Moving through kitchens. Through doorways. Casting scents and tastes over table tops and around conversations. Tracking heartache and years of travel, years on the road, to arrive here with you. With us.

We should be sewing ourselves into the tapestry of an immigrant’s journey. Weaving with food. Not throwing them away.

Immigrants do not deserve to be tossed into a swamp with all their stories and all their knowledge and all their dreams and all those historical and historic memories of their family tables.

We have so much to learn from each other. So much more to eat. Every person has this age old memory baked into their food. Baked into their minds. Home. Every immigrant you send to a camp has this.

Be kind.

Celi

If this meant something to you please consider sharing or restacking. That really means a lot to me. Thank you so much!

I'd like to add one more hand pie food called the pupusa from El Salvadore. We have 4 or 5 pupusarias in our towns. Tasty, like all the others.

Found you…. wondered where you’d gone👍