a washing basket moment

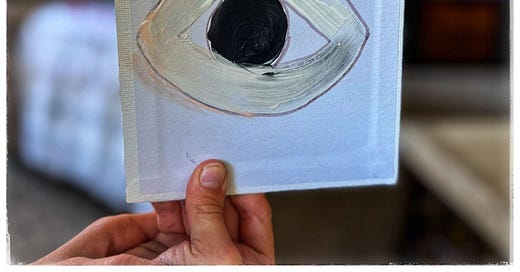

I call it the inner eye. The eye that sees and knows things. Quietly. Agelessly. The inner eye tracks cycles; cycles of the seasons, cycles of the moon, cycles of weather, cycles of blood.

Sometimes the inner eye will just sit you down and tell you things.

My son was talking to me the other day. On the phone. My eldest son. He and his dog Leroy do search and rescue up in the mountains of Canada and the search and rescue is often search and recover which is hard.

I said - you are having a washing basket moment.

He said - can you send me that story again.

I am leaving the USA (family stuff as you know ) and taking you with me on my travels through California, New Zealand, eventually washing up in Melbourne, Australia.

I will still be writing. I will still be narrating. This space will still be on active duty. We sometimes look back to stories from my younger lives to learn useful lessons for our present lives. Here is one.

For my eldest son.

The Washing Basket Moment

To carry a baby and a basket of washing is a juggle. When I was a very young mother, I had both in spades; babies and baskets of washing, that is. Plus juggling, I guess, when you think about it. Often, I put the baby in the washing basket with the clean laundry and carried them both outside to the clothesline. How to juggle the juggle.

On this summer day in rural New Zealand, a good forty years ago now, I hefted a basket of washing and its piggyback of giggly baby through the back door, down the steps of the old farmhouse, not the one from last week; this is another one) down the path that ran out to the garden and to the clothesline. The trees were alive with birds who sounded like children, and the fenced backyard was alive with children who sounded like birds. This was where my favourite flowers grew and all the herbs I had transplanted from the last house and the house before that. The garden was rich with the mid-morning summer scents of lavender, manuka, roses, and lemon balm. I had only been married a few years, but we had moved around so often in that time and even though I had left behind my friends, I had always brought my plants.

My world had shrunk just a bit more with every move and each new baby. This felt OK. I was busy.

The rotating washing line stood a little crooked and a little old in the yard. It was strung with many wires on a cross piece fir maximum space for hanging clothes. A cobweb of straight wire lines sat like an umbrella atop a long pole. Halfway down the pole was a crank handle so I could raise or lower the line. Already, three of the quadrants were full of a brilliant array of tiny white singlets and white pants and white cotton nappies. I loved to hang out washing. I loved the art of it—the exact loops, the sway of the fabrics, the combination of colours and shapes. I took as many photos of washing on the line as I did of children in those days. The daily remaking of this piece of living art made me smile, especially in the summer when the coolness of the wet fabrics mocked the heat of the day and drifted to and fro in the breeze. And it was a hot summer morning. So the clothes were drying fast. There is a cycle to laundry being carried out, hung up, brought down, and carried back in that is soothing in its ease. It’s lack of expertise. It is the first job of the day and the last one. Simple. An easy success.

I carefully put the overburdened basket on the grass under the line and reached for baby. On the lawn, in the shade, there was a playpen waiting with toys and his rug. He could sit up by himself now and had just begun to crawl, so I put baby in there. I poured a smear of water from a jug into a tray for him to play with and popped it in the corner for him to find. I checked for the other two children and noted that they were doing something down by the chook house. I could see them - they were quiet. I scanned for danger - everything was OK.

Then I began to unpeg dry, warm, fragrant, tiny articles of clothing from the lines, folding them and stacking them onto the laundry table next to the basket of new wet washing. My mother always said, “Don’t bend over more than you have to.” So I had a table under the line. As I took down a piece of dry clothing and set it down on the table, I would pick up a wet one from the basket and hang it in its place using the same pegs. My fingers were fast, my feet pivoting in a working dance, not wasting any movement. “Leave the pegs on the line,” she would say, “so they are waiting for the next piece.” My summer dress billowed in the slight breeze. My bare feet felt the green in the grass. You can feel green, you know. Laying dry clothes to the table, folded on the way down. Swoop down to the basket, wet clothes up to the line, peg, peg, unpeg, unpeg. Dry to the table, swoop down to the basket, wet up to the line, peg, peg. I used the old rhythm of all the women who had gone before me. It was a comfortable choreography, an unconscious rhythm - sleepy and fond.

Without much thought, I made sure to hang the clothes out in the order I would bring them in. When I hung the clothes, I would coordinate them into outfits so they came off in bundles of clothing ready to wear. “Hang them inside out,” Mum would say in her croaky voice, “so they don’t fade.”

I kept an eye on my children, though my mind had begun to slip its moorings. My inner eye was managing the moment just fine. I always called it the inner eye - that unconscious private looking. Thoughts we never shared because these thoughts did not become words. The ache in my back was still there, and I wondered at it. My inner eye looked deep inside to see what was causing the unbalance. My breasts rose in my dress. I had been pregnant often enough to know that something hidden was stirring. Everyone knows that mothers have three eyes - well, actually, four. Two that you can see in the front of your head. Mine are blue. Pale blue, actually. Then parents have the eye in the back of their head to see what the kids are up to. Then the inner eye, which just knows things. The inner eye tracks cycles—cycles of the seasons, cycles of the moon, cycles of weather, cycles of blood, cycles of fight and slaughter and calm. The inner eye is always on the watch for storms or sickness or hunger. The inner eye knows when someone is lost before your count comes up wrong. Our inner eye detects every change in our bodies, every need, and checks for balances.

Children’s noise was the soundtrack of my days. And the notes had changed alerting me to lift my head from my work. My two little boys had begun a very simple game where they dipped water out of the water barrel, then ran with little steps on short legs across the lawn - stooped over so the sandcastle buckets did not spill too much - then poured the sloshing water into a dip in the garden. Dropping the buckets, they kneaded the puddle very fast with their feet until it was a real mud puddle, then they grabbed each other’s arms and, as one boy, they jumped up and down as hard as they could, spraying mud all over themselves and each other. Shrieking as loudly as they could was part of the game. This had to be done fast because the water drained fast. Then off they would go with the buckets to get more water and do it all over again. I guess they were maybe three and four. So I would have been twenty-three or twenty-four.

Almost lunchtime, I thought. I can hose them down. Then nap time. Too young for school but not too young for mischief. Nap time for the lot of them. My inner eye opened slightly at the thought of that hour’s peace. This was when I did the housework at top speed and maybe got a sit-down with my book, a cup of tea, and my notebook for notes. My mother always said, “Rest when the baby rests.”

I bent to pick up another piece of wet washing from the second basket, too tired already to heave the whole basket up onto the table. It was a wet tablecloth. White. Everything was white in this new load. "Never, ever mix your colors with your whites," Mum would say.

I thought about some of the things my mother had said: Leave your hair long. Tie it up. Make me a cup of tea. Boil the potatoes for a few minutes before you roast them. You have to adopt this baby out - it would be cruel for you to keep him. You don’t know how. Anyway, you are not welcome to live here with a baby and no husband. Butter and the cream from the top of the milk for mashed potatoes. Don’t trust anything a man says after midnight. Boil the eggs in cold water. Never use cornflour to make a roux. Don’t tuck those sheets too tight. Hold your head up. Stand up straight. How could you get pregnant again? You will have to marry this one. At least he is Catholic. It takes two to tango. You made your bed, you lie in it. Don’t think so much. Keep your knees and ankles together when you are sitting. Get up. Buck up. Smooth your skirt before you sit down.

Without even thinking, I put the wet tablecloth completely over my head. I could still see light - I was breathing in diaphanous cool, wet air. Then I started to cry. I stepped backward and half fell, half sat, slumped into the basket of wet washing, my knees together and ankles to the side. I could feel the cold damp of the wet clothes seeping through my dress, and I cried and cried. The children’s hysterical game slipped away, the baby’s gurgles became muted, and I cried, I wished I was not there anymore. I did not want to be anywhere else or dead or anything. I was just so tired. So terribly tired.

I just wanted it all to stop - for a day, or an hour, or something - so I could catch my breath. So I could get a handle on what was happening, so I could reach for my rudder. It was all out of control. My inner eye was struggling to be heard. I was terribly young. I did not want to be anymore. I did not want to die. Or leave my kids. I just wanted to take my self off my body, detach, un-buckle, dislocate my brain and all my eyes and everything I had seen and had to see, and rest for a while.

My mother was dying, you see. She had been dying for a few years now. It was the cancer. She would die soon, they said. Though they had been saying that for years, too. She lived away at the beach in our big family home, six hours drive away. Every two weeks or so, I had been packing up my children to go and see Mum and help out. My father would drive up from the beach, collect the children and me, and we would drive back down the island together. We would drive through the night so the children would sleep.

I would stay a week to help with Mum and do all the things that needed doing - cook and put meals in the freezer, weed the garden, put food in jars, get the washing up to date, clean the house, change the sheets, do the shopping -while Mum played with the baby in her bed and the kids ran with my teenage brother on the beach. Then Dad would drive me back to tend to my husband and I would do it all over again - meals in the freezer, garden weeded, food in jars, washing done, washing out, washing in, house clean, sheets changed. Then after a few weeks Dad would come back, and we drove back down the island again. We had been running like this for months, Dad and I, the intervals away from Mum getting shorter and shorter as she slipped further into the quiet.

She did not fight death. She said “It is harder to watch others deal with my death than it is to die.”

Dad and the children and I drove back and forth. My husband was a busy man, you see. He worked very hard. He could not come with me. He did not appear to begrudge my time away, but I was too worn out to ask. Maybe too afraid of the answer.

I sat there on that beautiful late summer day, with my rear in a full basket of clean wet washing, a table-cloth over my head, my elbows on my knees, my head on my hands, my wrists in my eyes, stuffing tears back down my throat: my children playing under the trees. My mother was dying, slowly slipping into the holy waters, and I did not think I could bear it. I could not make sense of it.

I howled with my mouth open, absolutely silently. Not one thought in my head other than the feel of the wet washing, the terror of losing my mother, this terrible aloneness, and wishing I could feel nothing anymore. And that terrible, terrible knowledge that I was only me and had to be all these things, and do all these things and there was only me.

Soon, my tears wore me out, as tears do, and I came back to where I was. My inner eye, my self, shut the door gently behind me. Because young as I was, I was the bloody mother and I was the bloody daughter. And I felt bloody, as Mum sometimes said. “Bloody is a useful emotion”.

With my head still covered, I quietened and I listened carefully and the children were still where I had left them. I pushed the tablecloth up to the top of my head, winding it like a towel on wet hair, unwilling to give up its cool shade, and looked at my noisy, chubby baby. He was still sitting in his playpen, watching his brothers.

The dog had moved to beside the playpen and was watching me. A chook was perched on the edge of the playpen, watching the dog.

I turned to the baby’s brothers, and there they were, still heaving with laughter, jumping up and down in the mud. But now they both had their shorts on their heads - the shorts pulled over the tops of their heads, the waistbands slipping slowly down into their eyes, with their T-shirts sliding about on top of the shorts, their heads tilting further and further back so that they could see. Leaping in the mud and shrieking. Screaming. Laughing brilliantly. Like little dirty suns.

The eldest one saw me see him, and, laughing, pointed to his new headgear, then waved his arms in a circle, inadvertently knocking his brother clear off his feet and further into the mud. His grin was as bright as a giggle. Delighted that I had given him such a grand idea. His brother popped back up, his face covered in mud like a miner, and shot me a grin of teeth.

I sat for a while longer and watched them. Filthy children are always joyful. Filthy clothes can be washed.

It was almost lunchtime, then nap time, walks, then dinner, then bath, then bed. We would be traveling again in a few days. I needed to call home. Start packing again.

I rose with a sound - you know that sound. It is not a grunt or a sigh, just a rising sound. An "up we go" sound. I hung the tablecloth on the line, put out the rest of the wet washing, put the neat piles of dry washing into the basket, brushed down the baby, loaded him under my arm like a rugby ball, and walked back inside to make lunch, calling out to the others to go wash off under the hose. It would be warm from the sun.

Wind in the Willows: Chapter ELEVEN

Go here if you need to play catch up:

I hope you have all had a lovely Sunday or Monday - what ever day it is where you are.

I am in California on the first leg of my journey out of the USA. Working in the garden here where there is cool sun and so much green. Adjusting from the ice and snow of the Illinois farm to verdant green and vegetable gardens of the suburbs in Visalia is always a delight.

I am surrounded in the next generation of children baking and making messes. We have been making crepes and cheesy muffins.

And gardening. And art. Of course. Not much mud!

Back on the Farm

All is well back on the farm though I have only been gone a couple of days. I will have some pictures for you for next weeks newsletter.

Have a gorgeous day!

I must away!

Time to wash some clothes!

Love Celi

There were two families near the place where I grew up. One family had 12 children and the other had 13 children, there were just 3 children in my family. I never thought much about them because some of the families had children about the same age as me, so we all went to school together.

This is wonderful